If I asked you to guess the job title of someone coding an app for work, your first guess probably wouldn't be “writer”. It probably wouldn't be your second or fifth guess either.

The fact I wouldn't be the first person you think of doesn't offend me. None of my resumes have ever listed coding expertise as a skill. Most of what I know I picked up through work, which necessitates an understanding of technical language and an interest in programming trends. A little of what I know is osmosis from living in the Bay Area, where tech conversations are unavoidable for anyone with a social life.

But life is full of little surprises, and one of those is that I did in fact create an app for work. I'll add an unsurprising caveat: I didn't actually code it—instead it was created completely through vibes, doing what a lot of code curious folks are doing with vibe coding apps like Bolt.

“Vibe coding” as a concept only emerged in early 2025, but it's already one of the most talked-about usages of large language models. It's sparked a lot of debate on its effectiveness as a tool for coding and a lot of anxiety over how it will change the tech landscape, especially for junior developers. Even for experienced developers, it holds the existential threat of imposter syndrome, and past that complete replacement.

The promise that vibe coding will give anyone, even those with a nontechnical background, the power to create their own usable applications is also debatable. I can say that from my own experience. It felt like hitting one of those “That was easy!” buttons from Staples. But it was too easy, and immediately upon handing the output over to someone with more technical expertise than me, the holes began to show. While it may be a powerful tool in the hands of someone who knows what they're doing, in my hands it was like one of those AI filters that makes you look like a Studio Ghibli character: fun to post, but not actually substantive.

I created my “app” as part of Bolt's Hackathon. In collaboration with Reddit, the contest prompt was to create something silly that was irreverent and overall useless. I often have useless ideas, so it was perfect for me. “It's like Yelp but for bathrooms. And it's for the worst bathrooms in the world,” I told my mom. “Uh, what do you do for work again?” she replied.

The process for getting started was fairly easy. Or, it should have been fairly easy. For someone who doesn't know where the terminal is on her computer, it was not. Devpost, the hosts of the contest, touted that it would take me less than one minute to start building my application with Bolt. They had provided several resources for me to look through, including links to Reddit's Developer Quickstart. I ended up sinking a lot of time into that particular resource because I didn't know what I was doing. I'll take this time to formally apologize to the Help Desk at Stack Overflow for trying to download node.js onto my work laptop even though I definitely didn't need it.

When I figured out that Bolt could do everything I needed, it became much easier. That is a true statement, by the way. Bolt can create a simple app end-to-end almost seamlessly, as long as the person doing it has a rudimentary knowledge of code or clear instructions on what to run. I fell into the second category; I didn't have a clue about what commands I would need to make the program work until I read one of the Devpost resources. Whether the app would be any good was what I would find out.

Bolt's interface is sleek and intuitive, with a live preview of your creation on the side. It also allows you to look through your codebase and manually update lines as needed. For my purposes, I used the natural language prompt box, which came with some tips for efficient prompt engineering. I used none of them. My prompt was simply, “Create an app for Reddit that's like Yelp but for bad bathrooms.” (Come on, it's a joke app for bathrooms; I don't have to be an eloquent prompt engineer.)

My friendly vibe coding AI immediately started working, creating folders to dump code into. All in all, it took about ten minutes to create the foundation of what I had asked for. The app was launchable on my tester subreddit, including a slightly silly UI that used a toilet emoji. It had a place to leave reviews, a rating scale, and a page that would populate with reviews as people wrote them.

All of these things were automatically created in a lovely little UI I could click around in on my tester Subreddit. It also didn't work at all.

Almost immediately, error messages popped up in both my Bolt interface and the app itself. No matter how much I tried, I couldn't upload a bathroom review. I got several error messages in scary red text telling me that location services weren't available and that I wouldn't be able to upload a review. Although it had hardly been any work on my end, I did feel the sting of defeat. So I told my Bolt AI, “The app doesn't work.”

What came was about 45 minutes of troubleshooting, where the AI told me exactly where to find error messages. I didn't have to understand any of them myself; I just had to paste them into the dialogue box verbatim, unformatted, and Bolt would deal with the issue. And while Bolt did provide me with information on what it had fixed, it wasn't useful to me as a non-coder, who didn't know what it meant when API endpoints were not being served at the root level. I'm sure if I had any understanding of what exactly was happening inside my app, I could ask it to dig deeper, but the whole point of this experiment was that I didn't.

My lack of understanding went beyond the codebase and to some of the basics of testing and working with my app. For instance, I didn't realize the `npm run dev` command would update the existing tester app in my tester subreddit. I thought I had to relaunch and repost the app every time edits were made to test a new “version” of the app. In my head, each version of the app was its own respective entity, as opposed to an evolving application that would update itself. Because of this, my tester subreddit had 20 posts on it by the time I had an actual working toilet app.

But Bolt was a powerful helper. I cannot overstate how lost I was in the process of creating this application and how easy Bolt made it for me to make something. It even helped me make simple changes to the interface, allowing me to play with the design in a way that was more comfortable for me as someone with a graphic design background.

Eventually, I made something that worked, with the use of the word “I” being loose. Really, Bolt had created something; all I had done was give it a prompt and feed it error messages when it asked me to. With each iteration of the application, more and more started to work. I was able to input information, look through reviews, and even add little flourishes like a Bolt badge and different review options.

But even with the app live and working, was it any good?

I felt I had fulfilled the challenge posed by the hackathon competition: I had created something silly, irreverent, and totally useless. Immediately, my coworkers started inputting some of their least favorite bathrooms. It was a ball, for sure.

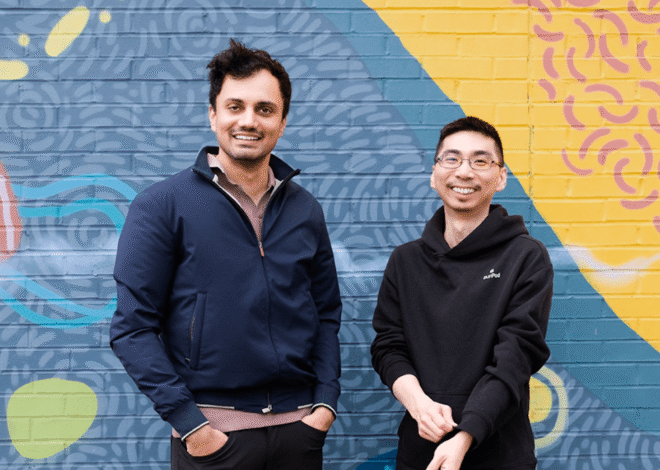

When I met with Ryan Donovan, who you definitely know if you've ever listened to our podcast or read anything on the blog, to review my app, the holes started showing immediately. To start with, he was pleasantly [Ed. note: I don't know if “pleasantly” is the right word here] surprised by how many technologies were being used in my simple app. He asked if I knew what JSON or Redis were, as they were both formats being used to run my toilet application. My answer was a resounding no.

Ryan didn't even need to look at my actual code to find issues. He could find glaring ones just from visiting my testing Subreddit and hitting the inspect feature. He let me know right away that my application was ripe for hacking, as there were no security features present to stop someone from accessing any of the data it was storing. This is obviously a big deal, but I'll get back to it later.

As part of my edification, Ryan suggested I get feedback on the code itself. He mentioned posting it publicly to GitHub and asking the community to give me feedback, but as I started to understand just how bad what I had created was, I shied away from the idea of a public lashing. It wasn't that I was afraid to kill my darling; in fact, there was no darling to be killed. It was more of a simmering feeling of dread, the kind one gets when they know they didn't do their homework very well and are afraid of what the teacher will say.

Luckily, I live in the Bay Area, which means almost all my friends are developers. So before I let strangers play around in my code, I turned to them. It was a cowardly move, because the added layer of context meant that my friends would go easy on me, knowing that my creation was vibe coded and that I probably didn't understand any of the feedback they were giving me.

The main piece of feedback from my friends was that the code was messy and nearly impossible to understand. I intentionally gave them little context on what was being built, instead letting the `.readme` that Bolt created for my project speak for itself. The lack of organization started there, mainly because I have no experience using GitHub. “You have a nice readme, but for some reason you buried everything inside `./project`,” one of my friends, a software engineer in Palo Alto, wrote. “Would you consider putting all that stuff in the top level, so people can see everything automatically when they visit your repo?”

Another friend wrote, “All the styling is inlined into the `tsx` components, which makes it much more cluttered/hard to read.” I didn't know if that meant I had done something wrong in my GitHub upload or if the code itself was the issue. Her overarching piece of feedback was that the code wasn't created in a way that facilitated feedback or understanding: “For example, the block of code that is returned from `LocationDetails.tsx` is huge. I would split it into several smaller components.”

Then at the end she added, “There are no unit tests.” I took this to mean that she couldn't understand if the components of what I had created even made sense, or could exist on their own. That, I thought to myself, was probably not good.

A clear disconnect then stood out to me between the vibe coding of this app and the actual practiced work of coding. Because this app existed solely as an experiment for myself, the fact that it didn't work so well and the code wasn't great didn't really matter. But vibe coding isn't being touted as “a great use of AI if you're just mucking about and don't really care.” It's supposed to be a tool for developer productivity, a bridge for nontechnical people into development, and someday a replacement for junior developers. That was the promise.

And, sure, if I wanted to, I could probably take the feedback from my software engineer pals and plug it into Bolt. One of my friends recommended adding “descriptive class names” to help with the readability, and it took almost no time for Bolt to update the code. It even had an innate understanding of why I might want to add descriptive classnames, something I wouldn't have understood unless my friend had explained it to me.

But what if I wasn't someone with developer friends? What if the project I was working on wasn't just for the fun of it but instead something I was really passionate about, or even wanted to bring to market?

The mess of my code would be a problem in any of those situations. Even though I made something that worked, did it really? Had this been a real work project, a developer would have had to come in after the fact to clean up everything I had made, lest future developers be lost in the mayhem of my creation. This is called the “productivity tax,” the biggest frustration that developers have with AI tools, because they spit out code that is almost—but not quite—right. Our Developer Survey found that 66% of developers experience this tax when they use these coding tools.

But even if we weren't to worry about my good buddies down at engineering, there is an even bigger problem: security. I want to touch back on the point that Ryan made about none of the data being protected on my silly toilet app. Luckily, in this case at least, no data of importance is being shared or stored on my application. But there are many instances where this would not be the case.

Because these tools are promising powerful results without the need for developer experience, there are probably a lot of people without experience who will use something like Bolt to create their passion projects. And probably a lot of these passion projects will be well-meaning, and will work, on the front end at least. And maybe some of these programs will ask for information like ZIP code, or email address, or date of birth, or to even create a password. You can probably see where I'm going here; GDPR can too.

It does seem unlikely that something that's going to be pushed to market would go live without having someone with a development background look at it, but what of the fun side projects like mine? I could easily imagine an evil world where someone vibe codes something for their loved ones that includes identifying information about the people in their lives, and that falls into the hands of malicious folks who know how to use the inspect function.

Was what Bolt created good enough for my purposes? Sure. And with the help of a few knowledgeable friends and coworkers, could I have fixed the issues I had with security and organization without ever having to learn a single command? Yes, definitely. But for a technology that is supposedly going to make junior developers obsolete, it needed a lot of help from my friends—all of whom are junior developers.

On the other side of this story, I want to share something about one of my best friends who also regularly vibe codes. He's a theoretical physicist with a doctorate from Stanford. He had wanted to remain in research after finishing his PhD, but found the opportunities slim and the pay even slimmer because of the current state of higher education. So he pivoted, pretty hard, into a role that meant he had to learn how to code quickly.

He shared with me that LLMs had increased his learning capabilities ten-fold because they allowed him to find information fast. He talked about his mish-mashed usage of CoPilot, Gemini, and ChatGPT almost like it was a fond tutor of his, referencing times when he couldn't figure out a bug and so had Gemini explain it to him. This, he told me, helped him the next time he experienced a similar bug.

This, I think, is the real promise of vibe coding tools—that you can learn how to code without a CS degree. There is no one in the world who would say my friend isn't intelligent enough to code, but the issue was that he had no experience. And after five years in the Stanford physics department, there was no way he was going back for another degree. Vibe coding tools were giving him the support and knowledge he needed, so he could learn these skills himself.

Like anything in the wild west that is this age of AI, it all depends on how you use it.

To take a page from my friend, I want my vibe coding experience to be the first step in me learning how to code. So, I'm offering up my vibe code for feedback, criticism, and tips from the community. Let me know what you think of my GitHub, and what you think I should do next to stop being the worst coder in the world.