I was at an institutional investor conference back in 2011.

The stock market had recovered somewhat from the depths of the 2008 financial crisis but plenty of investors were still licking their wounds. No one was pounding the table to buy stocks.

In fact, a well-known hedge fund manager got up in front of the crowd and told everyone, “I have bad news for you…”

He then went through a series of charts and historical data that showed how overvalued the stock market was. The CAPE ratio was featured prominently and looked like this at the time:

I don’t recall the exact figures, but he told the crowd we were somewhere in the 90-something percentile of worst valuations ever. The prospects for forward returns from those levels in the past spelled trouble. Combined with low bond yields, investors were looking at a decade of low returns.

That was his forecast anyway.

This well-known investor wasn’t alone in setting low expectations for future returns. The CIOs in the crowd mostly agreed with him. No one expected a rip-roaring bull market to last for well over a decade at that point.

Sam Ro has a great piece at TKer that looks at what went wrong for the predictive power of the CAPE ratio. Sam pulled some old quotes from CAPE creator, Robert Shiller:

“I’ve been very wary about advising people to pull out of the market even though my CAPE ratio is at one of the highest levels ever in history,” Shiller told Bloomberg in April 2015. “Something funny is going on. History is always coming up with new puzzles.”

Shiller’s been warning people against leaning on CAPE for a while.

“Things can go for 200 years and then change,” he said in a 2012 interview with Money magazine. “I even worry about the 10-year P/E — even that relationship could break down.”

That was a good bit of humility on his part. The stock market didn’t care about the previous 10 years’ worth of earnings when tech companies were about to rewrite the rules of profit margins and market domination.

Just because something worked in the past doesn’t mean it will work in the future. Even if something does work reasonably well, it’s not guaranteed to work every time. Always and never are two words you should drop from your vocabulary as an investor.

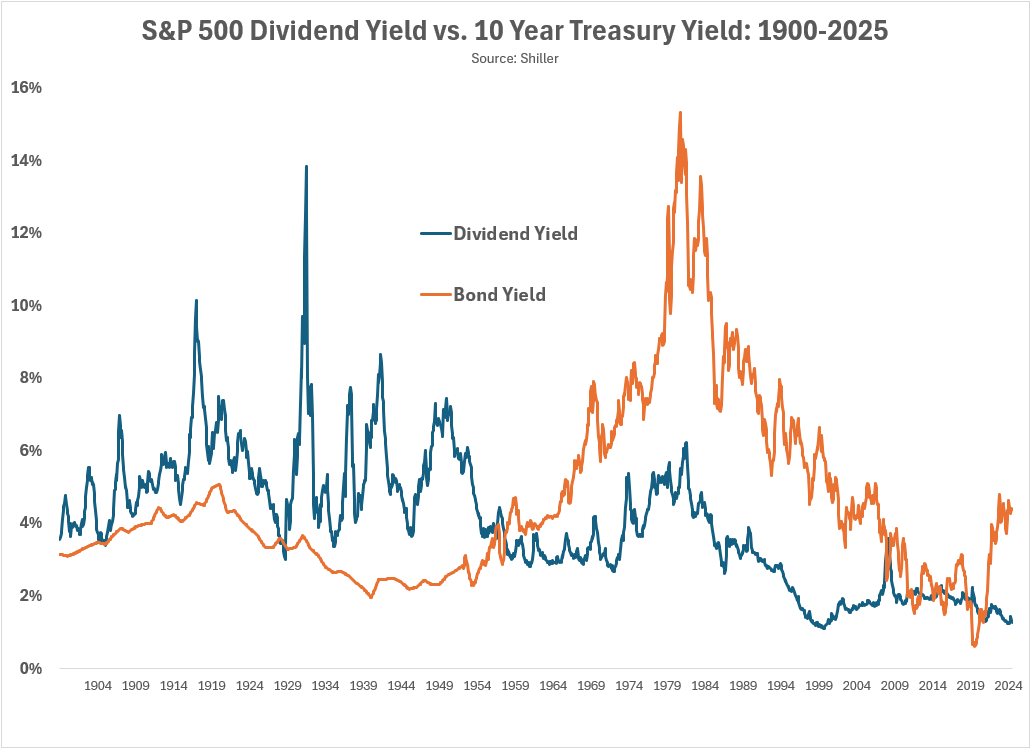

Peter Bernstein wrote about something that worked until it didn’t in his classic book Against the Gods:

In 1959, exactly thirty years after the Great Crash, an event took place that made absolutely no sense in the light of history. Up to the late 1950s, investors had received a higher income from owning stocks than from owning bonds. Every time the yields got close, the dividend yield on common stocks moved back up over the bond yield. Stock prices fell, so that a dollar invested in stocks brought more income than it had brought previously.

So it is no wonder that investors bought stocks only when they yielded a higher income than bonds. And no wonder that stock prices fell every time the income from stocks came close to the income from bonds.

Until 1959, that is. At that point, stock prices were soaring and bond prices were falling. This meant that the ratio of bond interest to bond prices was shooting up and the ratio of stock dividends to stock prices was declining. The old relationship between bonds and stocks vanished, opening up a gap so huge that ultimately bonds were yielding more than stocks by an even greater margin than when stocks had yielded more than bonds.

Take a look:

Bond yields never stayed above dividend yields until they did. Then it happened for five decades.

Things change.

The inverted yield curve was 8-for-8 at predicting preceding recessions…until 2022 that is. Short-term bonds yields went above long-term bond yields but a recession didn’t follow. The yield curve has since un-inverted and still no economic downturn.

That same year stocks and bonds did something that had never happened before — they both crashed. Investors assumed bonds always hedged a falling stock market. Not when bonds cause stocks to fall.

Benoit Mandelbrot once said, “The trend has vanished, killed by its own discovery.”

The hard part about all of this is that sometimes trends change forever, and they don’t go back. Other times, there are exceptions to the rule because nothing works all the time.

There is a fine line between discipline and an inability to be flexible as an investor.

The solution here is to avoid going to extremes. There is a lot of gray area between 0% and 100% certainty.

Spread your bets.

Strong opinions loosely held.

And go into any investment strategy, historical market backtest or economic relationship with an open mind.

The market will humble you if you don’t approach it with a sense of humility.

Further Reading:

The Half-Life of Investment Strategies